Information Systems in the Living Room: A Case Study of Personalized

Interactive TV Design

Georgios Lekakos

eLectronic Trading Research

Unit (eLTRUN)

Athens University of

Economics & Business

47 Evelpidon & Lefkados

Str.,

113 62 Athens, Greece

Tel: +30(1)8203663

Fax: +30(1)8203664

glekakos@aueb.gr

Kostas Chorianopoulos

eLectronic Trading Research

Unit (eLTRUN)

Athens University of

Economics & Business

47 Evelpidon & Lefkados

Str.,

113 62 Athens, Greece

Tel: +30(1)8203663

Fax: +30(1)8203664

chk@aueb.gr

Diomidis Spinellis

Department of

Information and Communication Systems

University of

the Aegean

GR-83200

Karlovasi, Greece

Phone:

+30(273)82222

dspin@aegean.gr

The birth of the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1993,

particularly its graphical user interface, offered marketers opportunities that

were previously unimaginable. The WWW allows for advanced marketing activities

and, moreover, for interactive marketing, as the user is actively involved in

responding to the vendor’s promotion campaign. Interactive TV, also referred to

as iTV, combines the appeal and mass audience of traditional TV with the

interactive features such as those currently available on the Web and offers

new possibilities for the viewer, who can directly access relevant information

and other services being just ‘one-click’ away. While personalisation is a

practice used widely on the Internet by many sites that exploit the huge amount

of customer information they collect, applying personalisation techniques over

interactive television presents a number of obstacles. In this paper we focus

our attention on the design and testing process of the User Interface (UI) for

the Interactive & Personalized Advertisement TV viewer. The challenges of

designing interactive TV applications are based on the differences of the

medium from the traditional PC based Information Systems in terms of input and

output devices, viewing environment, number of users and low level of expertise

in PC usage.

1

Introduction

As

digital technology and consumer behaviour evolve, marketers can and need to

continuously enhance the value of their digital marketing offering. The birth

of the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1993, particularly its graphical user interface,

offered marketers opportunities that were previously unimaginable [Poon and

Jevons, 1997].

Interactive

TV, also referred to as iTV, combines the appeal and mass audience of

traditional TV with the interactive features such as those currently available

on the Web [Developer, 1999] and offers new possibilities for the viewer, who

can directly access relevant information and other services being just

‘one-click’ away. For the marketer, the great potential of interactivity rests

in the capability it offers for better understanding the viewer’s behaviour and

building personalised relations with individual consumers. As the case of the

Internet has demonstrated, tracking the user’s interaction with the system,

including navigation, content preferences, purchasing habits etc., can greatly

support many of a marketer’s objectives and activities. These many be:

measurement of interactive advertisement effectiveness, better understanding of

consumer needs and preferences, effective targeting of advertisement and,

ultimately, personalisation of advertisement messages, site content and

services.

In

the context of iTV advertising, personalisation refers to the use of technology

and viewer information in order to tailor commercials and their respective

interactive content to each individual viewer profile. Using such viewer

information, either obtained previously or provided in real-time, the stream of

advertisements adapts to fit that viewer's needs, whether they are stated

directly by the user or they are inferred by the advertiser.

While

personalisation is a practice used widely on the Internet by many sites that

exploit the huge amount of customer information they collect, applying

personalisation techniques over interactive television presents significant

obstacles:

1. Broadcast environment:

unlike the Internet, where each web-page is delivered individually to each

user’s computer upon request, iTV content is broadcast to all TV sets.

Delivering personalised content over a broadcasting platform is a contradiction

in terms. This would require transmitting as many streams as the different TV

sets. Thus, other techniques need to be applied in order to make this happen.

These techniques typically involve a set-top box or other similar terminal

device that stores some personalised content and controls the interactivity.

2. Targeting individuals:

Whereas the personal computer typically has only one user at a time, the

television is often viewed by groups of people in both private and public

areas. Consequently, personalising and targeting advertisements effectively

presents technological, business-related and practical challenges. Even if we

only consider household viewership, it remains a difficult issue how to identify

and target individual household members or whether to target the whole

household as a group. While it is technically possible to identify which

member(s) of the household is (are) currently watching TV (e.g. through ‘hidden

eye’ technologies or remote-control functionality), this is something not

perceived positively by viewers.

3. Viewing environment: TV viewing experience usually occurs in the

relaxing home atmosphere, mainly for entertaining or informative

purposes. Any interface that requires computer-usage experience will not match

to the average viewer profile. The input device (mainly remote-control) offers

limited functionality and the TV set as display (output) device has certain

restrictions in terms of appearance of data, fonts, colours (closely related to

the viewing distance). Nevertheless, in order to implement interactive and

personalized advertising, the Information System comprising the backbone of

that platform, should be supported in terms of functionality from a minimalist interface provided to the Viewers.

In

this paper we focus our attention on the design and testing process of the User

Interface (UI) for the Interactive & Personalized Advertisement TV viewer.

The challenges of designing interactive TV applications are based on the differences

of the medium from the traditional PC based Information Systems in terms of

input and output devices, viewing environment, number of users, low level of

expertise in PC usage. The multiple design alternatives must be evaluated for

specific user communities and for specific benchmark tasks. A clever design for one community of users

may be inappropriate for another community. An efficient design for one class

of tasks may be inefficient for another class. Therefore, the approach to the

UI design process is heavily based on User requirements provided by the Users

and the implementation of general IS UI design theory, principles and

guidelines in the challenging TV Viewing environment and finally the continuous

evaluation of the interface in terms of usability. All these, more often than

not, conflict with each other, so we provide the basic parameters –tasks,

users, interaction devices input/output characteristics, etc- in order to

balance the tradeoffs and make decisions about the form and function of the UI.

Human Computer

Interaction fundamental principles are presented in the next section along with

the major characteristics - differences between Television and Computers and

the usability methods among which the appropriate ones will be selected, in

section 3 a comprehensive description of the methodology employed for the

design of the User Interface and the challenges faced during the UI design are

presented, in section 4 a specific example of the design is presented, in

section 5 the evaluation methodology and the testing results and finally

section 6 includes the conclusions and further research.

Human-computer

interaction (HCI) is the scientific field related to usability of systems.

Described by Dix [Dix, 1996] as the study of people, computer technology and

the ways these influence each other. Preece et al [Preece et al, 1994]

defines usability as a measure of the ease with which a system can be learned

or used, its safety, effectiveness and efficiency, and the attitude of its

users towards it. In the early days of computing the majority of users were

technical experts whereas nowadays users have a wide range of knowledge and

experience, making usability a very important design consideration. Underlying

all HCI research and design is the belief that the people using a computer

system should come first. Their needs, capabilities and preferences for

performing various activities should inform the ways in which systems are

designed and implemented. People should not have to change radically to “fit in

with the system”, the system should be designed to match their requirements.

[Bevan, 1990].

User Centered

design is a wide spread practice in the domain of User interface design.

According to Bevan et al [Bevan, 1990] a User-centered design is an approach to

interactive system development which focuses specifically on making systems

usable and safe for their users. User-centred systems empower users and

motivate users to learn and explore new system solutions. The benefits include

increased productivity, enhanced quality of work, reductions in support and

training costs and improved user health and safety. Preece [Preece, 1994]

defines the objective of the user centered design as the system production that

are easy to learn and use by their intended users, and that are safe and

effective in facilitating the activities that people want to undertake.

In order to meet the goals

of usability there are many principles, guidelines and rules to follow.

Principles offer high-level advice to the designer that can be applied widely.

Guidelines are more general, often based on psychological theory or on

practical experience. They may come from diverse sources such as journals,

books, in-house manuals, etc. Guidelines may contradict each other and will

require a certain amount of judgement in their use.

The main principles of HCI given by Preece et

al [Preece et al, 1994]:

§

Know the user population

§

Reduce the cognitive load

§

Engineer for Errors

§

Maintain consistency and clarity

Another set of well known principles are

Schneiderman's [Schneiderman, 1998]

eight golden rules of dialogue design:

§

Strive for consistency: The definition of consistency is elusive

and has multiple levels that are sometimes in conflict. It is also sometimes

advantageous to be inconsistent.

§

Enable frequent users to use shortcuts: As the frequency of use

increases, so do the user’s desires to reduce the number of interactions and to

increase the pace of interaction.

§

Offer informative feedback: For every user action, there should be

system feedback. For frequent and minor actions, the response can be modest,

whereas for infrequent and major actions, the response should be more

substantial.

§

Design dialogs to yield closure: Sequence of actions should

be organized into groups with a beginning, middle, and end.

§

Offer error prevention and simple error handling: As much as

possible, design the system such that users cannot make a serious error; for

example prefer menu selection to form fill-in and do not allow alphabetic

characters in numeric entry fields.

§

Permit easy reversal of actions: As much as possible,

actions should be reversible. This feature relieves anxiety, since the user

knows that errors can be undone, thus encouraging exploration of unfamiliar

options.

§

Support internal locus of control: Experienced operators

strongly desire the sense that they are in charge of the system and that the

system responds to their actions.

§

Reduce short-term memory load. The limitation of human

information processing in short-term memory (the rule of thumb is that humans

can remember “seven-plus or minus-two chunks” of information) requires that

displays be kept simple.

These underlying

principles must be interpreted, refined, and extended for each environment.

An important

aspect in the design of TV Viewer Interface is to understand the

characteristics of the Television in comparison with the characteristics of

Computers in order to provide further insights for the design of this novel TV

UI. The following table (Table

1) compares television and traditional computers along

a number of dimensions.

Table 1 A comparison between TV

and Computers along several dimensions affecting the User Interface design

(Source: Jacob Nielsen, “Useit.com”)

|

Characteristic

|

Television

|

Computers

|

|

Screen resolution (amount

of information displayed)

|

Relatively poor

|

Varies from

medium-sized screens to potentially very large screens

|

|

Input devices

|

Remote control and

optional wireless keyboard that are best for small amounts of input and user

actions

|

Mouse and

keyboard sitting on desk in fixed positions leading to fast homing time for

hands

|

|

Viewing distance

|

Several meters

|

A few inches

|

|

User posture

|

Relaxed, reclined

|

Upright, straight

|

|

Room

|

Living room, bedroom (ambiance

and tradition implies relaxation)

|

Home office

(paperwork, tax returns, etc. close by: ambiance implies work)

|

|

Integration opportunities

with other things on same device

|

Various broadcast shows

|

Productivity

applications, user's personal data, user's work data

|

|

Number of users

|

Social: many people can

see screen (often, several people will be in the room when the TV is on)

|

Solitary: few

people can see the screen (user is usually alone while computing)

|

|

User engagement

|

Passive: the viewer

receives whatever the network executives decide to put on

|

Active: user

issues commands and the computer obeys

|

Table 2 presents a summary of the usability inspection

methods, necessary to perform in order to meet user’s needs. It is apparent

from the table that the methods are intended to supplement each other, since

they address different parts of the usability engineering lifecycle, and since

their advantages and disadvantages can partly make up for each other. It is

therefore highly recommended not to rely on a single usability method to the

exclusion of the others.

There are many

possible ways of combining the various usability methods, and for each design

we may need a slightly different combination, depending on its exact characteristics.

The choice of a usability evaluation method depends on the following:

§

Stage of design (early, middle, late)

§

Novelty of project (well defined versus exploratory)

§

Number of expected users

Table 2 Summary of the usability methods (Source: Jacob Nielsen,

"Usability Engineering")

|

Method

Name

|

Lifecycle

Stage

|

Users

Needed

|

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

|

Heuristic evaluation

|

Early design

|

None

|

Individual usability

problems

|

No real users

|

|

Performance measures

|

Competitive analysis

|

At least 10

|

Results easy to compare

|

Does not find individual

usability problems

|

|

Thinking aloud (coaching)

|

Formative evaluation

|

3-5

|

Pinpoints users

misconceptions

|

Unnatural for users

|

|

Observation

|

Task analysis, follow-up

studies

|

3 or more

|

Suggests function and

features. Reveals users’ real tasks

|

No experimenter control

|

|

Questionnaires

|

Task analysis, follow-up

studies

|

At least 30

|

Finds subjective user

preferences.

|

Pilot work need (to

prevent misunderstandings

|

|

Interviews

|

Task analysis

|

5

|

Flexible, in-depth attitude

and experience probing

|

Time consuming. Hard to

analyze and compare

|

|

Focus groups

|

Task analysis, user

involvement

|

6-9 per group

|

Spontaneous reactions and

group dynamics.

|

Hard to analyze

|

|

Logging actual use

|

Final testing

|

At least 20

|

Finds highly used features

|

Analysis programs needed

for huge mass of data. Violation of users privacy.

|

|

User feedback

|

Follow-up

Studies

|

Hundreds

|

Tracks changes in user

requirements and views

|

Special organization

needed to handle replies

|

In

this section we present our approach towards personalised interactive TV

advertisement that has been developed as part of the iMEDIA (Intelligent

Mediaton Environment for Digital Interactive Advertising) research project.

iMEDIA aims to provide an intelligent mediation platform for enhancing consumer

and supplier relationships, by establishing the necessary methodologies,

practices and technologies for: a) The broadcasting of personalised interactive

advertising to targeted consumer clusters, providing gateways for access to

product catalogues in other digital

environments b) The analysis of interactive consumer behaviour for

assessing advertising effectiveness c) The empowerment of TV audience as

interactive viewers and active consumers with total control over their private

personal information.

Figure 1: Prototype Design Methodology

Figure 1: Prototype Design Methodology

Our approach for

the development of the first iMEDIA viewer interface prototype consists of

three phases (Figure

1). The input for the first phase are the User

Requirements collected in facilitated workshops by iMEDIA partners representing

the whole range of the Interactive TV Business Model (Advertisers, Advertising

Agencies, TV Channels, Technology Providers) as well as consumer surveys in

Greece and Italy in May 2000 The objective of this method was - through an

iterative process – to refine and complete the initial requirements in order to provide input for

the development of the system. Also, at the first phase a paper mock –up has

been developed which has been based on the UI design Principles, the TV

Usability requirements. In the next phase the paper mock –up has been subject

to Expert (Heuristic) evaluation in order to remove early usability problems

and proceed with the development of the User interface using Macromedia

Director in order to incorporate videos and prepare a scenario as close as

possible to the actual TV Viewing experience. Entering the third phase, the

usability testing was performed using Focus Groups and Coaching one-to-one

method.

Design Challenges

In designing

iMedia user interface we faced hard choices on a number of issues. These include navigation, the appearance of

messages and on-line help, reversibility, the availability of a special

administrator profile, and the choice between using on-screen soft-keys versus

the use of specialized remote control keys, as presented below.

Navigation: The user should

always be aware of where he/she actually is, what he/she can do, where he/she

can perform and where he/she came from. Within the assessment of input devices

the well-known remote control has turned out to meet the requirements in the

best way, assuming the appropriate graphical UI. The navigation concept of four

arrow keys jumping a focus on the active controls on the screen has proved to

be the best solution for interactive TV applications.

TV Program: In our point of

view the point of reference when designing UIs for the iTV should remain the

traditional TV program -for some time to come at least. Interactivity should be

minimal and performed around the TV program. Therefore, we suggest the use of

pop up –in front of the video- menus and picture in picture functionality

wherever there is a strong need for full screen interactivity (e.g. form

fill-in)

Messages: Tasks with high

frequency of use should have a few confirmation messages, or reside just on

status messages –running in parallel with the current interaction. Ideally, we

should minimize fatal actions. Error

messages should be eliminated. Instead, we should prevent error and assist the

user for task completion or exiting from menu hierarchies.

Online help: This would be

achieved with the display of an optional tool tip bar, which presents short

help about the highlighted item. Furthermore a remote control button or a

special per menu item could provide access to in depth help.

Hardwired vs. Softwired UI: There is a

trade-off between the existence of special function keys on the remote and

hiding the functionality and the access to it, in an on-screen UI. An example

of the latter is the OpenTV case (www.opentv.com), while the

former is -partially- encapsulated in the WebTV case (www.microsoft.com/webtv).

Reversing actions: The existence of

an undo/back button, will allow users to explore in more confidence interactive

content, as they could always reverse their last action.

Menus &

Forms: We suggested the use of menus for the navigation among the main iMEDIA

choices. The menus are laid over the current TV program. The menu navigation is

performed with the cursor and selector keys. Menus are complemented with forms

in cases where user input is required.

Input Devices: Information systems that use the TV as

their interaction mechanism differ in a pervasive number of ways from

traditional systems based on personal computers. Since the interface is

designed with an interactive television setting in mind, the natural choice for

an input device is some kind of remote control. The user must be able to carry

out all actions available in a whole range of interactive television services

using the same device, including controlling a video (pause, rewind etc.),

entering a personal code and moving a pointer/cursor. Most television users will

not use a keyboard, because it is cumbersome to use while sitting on a couch or

a chair. Next, we discuss some alternatives for alphanumeric input.

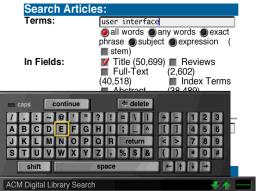

- Virtual Keyboard: The virtual keyboard (Figure 2) solution is very effective with

naïve users. Except from cursor movement and selection, no further

knowledge is needed. The virtual keyboard is slow and confusing with

expert users.

Figure 2 Microsoft's WebTV virtual

keyboard

§

Mobile Style of Text Input: Alphanumeric input with the numeric keypad of

the remote control would be invalid, unless mobile phones and SMS have been so

successful worldwide. The mobile style –or SMS- of text input proves both

familiar and relatively fast for all categories of users.

-

Remote Control: Remote control is the

preferred and most popular input device for iTV. Early iTV designs should

reside on this form of input, in order to keep low the cognitive load

imposed on computer illiterate people. We have been based on a fairly

common remote control, which is found in the TiVo set top boxes (Figure

3).

Figure 3 Remote Control for the

iMEDIA prototype

Output Device: The resolution

and screen display characteristics of a TV screen are significantly less than

that of most computer monitors. Pages that are designed for the PC screen will

be unattractive of even unreadable on a TV. Also, certain backgrounds display

distorted and unreadable on TV screens. In general, people who watch television

sit further away from their screens than those who sit in front of a computer

monitor. To make it easy for viewers to read and understand interactive

content, authors need to avoid small font sizes.

The iMEDIA Viewer

interface has been based on the Use Cases [iMEDIA Deliverable 1.4], which is a

formal description of the User Requirements, collected at the first phase of

the project. In the following for demonstration purposes we briefly present the

design of the ‘Activate/Deactivate

Viewer’ Use Case.

|

Use Case

|

Activate/Deactivate Viewer

|

|

Description

|

The purpose of this use

case is to illustrate the action taken by the viewer in order to activate

his/her profile. When a viewer sits in front of the TV set, he/she has to let

the set-top box know who is watching. The system presents a list of profiles

and lets the user select his/her identity.

|

|

Interaction Style

|

Direct manipulation

|

|

Attributes

|

Profile icons

|

|

Appearance

|

Semi-transparent overlaid

to a part of the TV screen.

|

|

Issues

|

Ideally

advertisers would like to know who is in front of the TV just before the

advertisement break, in order to serve targeted advertising. Interface

alternatives:

§

display an intrusive menu with profiles overlaid to the program a few

seconds before the break.

§

Use the number keys for selecting profile, although there is a

conflict with the use of number keys as TV channel selectors. Alternatively

we can use the arrow and selector keys.

§

overlaid menu remains for a timeout period of 5-10 seconds, which is

reset for every key press, so that more than one viewer have the time to

indicate their presence.

|

|

User Action

|

System Response

|

|

|

User watches normal

program flow.

|

A few minutes before the

next ad break, a set of icons, representing profiles appears on the TV,

prompting for activation.

|

|

|

Remote control holder indicates –optionally- his/her presence.

Furthermore he/she can indicate the presence of others, too.

|

Active profile-icons are

highlighted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4: Activate Viewer list of profiles

5

User-Test Methodology

and evaluation results

In this section

we describe the methodology used for the evaluation of the Viewer Interface

(mock-up demo). A concrete methodology is based on sound objectives, relative

to the stage and the general objectives of the project. Test environment

set-up, facilities, staff is described and measured tasks are defined. Finally

we define user profiles and results analysis approach.

Before starting

the testing session, all users attended an introductory presentation of the

system functionality and were shown the testing sessions content. The objective

of these practices was to eliminate as soon as possible the learning curve,

which every new system imposes to its users. In doing so, we expected to reduce

the non-sampling errors, and research bias that are usually present in the

introduction of breakthrough technologies.

The users were

asked to perform three scenarios, as defined in the use cases. In each case, we

use the same videos sequences, so the users remain focused in the interface

elements being tested. We have also used ordinary and common –to the Greek

audience- program and advertisements for the –same- reason of user engagement with

the tested elements. Finally, the scenarios used are a replication of the

normal TV flow of a program, interrupted by ads and then continued, in order to

provide a relevant and familiar –to the current TV experience- testing

environment.

§

Activate/Deactivate Viewer, Bookmark and

Contact me: The user is asked to watch a program flow, which is interrupted by a

set of three advertisements. This scenario starts with the normal program,

which at a certain point of time is overlaid with an activate/deactivate user

system request. The user is expected to press the corresponding to his/her

profile remote control button, in order to indicate his/her presence. Then

comes the advertising break whereas, the second ad contains a “bookmark” and a

“contact me” button. By pressing the “contact me” button, a consumer request

form appears which confirms the promise of the advertiser to get in touch with

the consumer, through an alternative medium –email, phone, etc. Then the

program is continued upon an assumed ending. The user is expected to become

aware of the existence of added value services and understand the implications

of his/her confirmation. If the user clicks the bookmark button, he/she is

asked by the system to indicate his/her profile, and the currently transmitted

advertisement is stored in the Set-top box for viewing later, at viewer’s

convenience. Following the end of the advertisements break the program

continues.

§

Interact with Advertisement: We assume that the user has bookmarked several advertisements during the

previous sessions. The user is asked to take the initiative to interact further

with one of them. The user is expected to open the main menu and navigate to

one of the bookmarked advertisements. Then, browse through the pages of the

interactive ad and complete the session by returning to the normal program

flow. During the menu selection process, the normal program continuous in the

background.

§

User Profile Management: We assume that

several member profiles have been inserted in the system. The user is asked to

perform a set of actions relative to his/her profile. These include viewing the

sections of his/her profile and editing a specific field. The user is expected

to navigate through the profile management menus and forms.

At this stage in

the development of the iMEDIA TV viewer interface the most appropriate methods

for user testing –as explained in a previous section-, are the focus group and

coaching sessions. These two methods give complementary results. The former

stimulates group dynamics and reveals new issues, while the latter allows for

in depth interviewing of specific user profiles, along the dimensions defined

through heuristic and focus group evaluation.

Focus Group Key Findings

The main points

of the focus group results are summarized in the following:

§

In general, the focus group downplayed on the importance of the iMEDIA

menu system and profile management functionality. The rationale for both

positions was the low task frequency and the high penetration of mobile phones

and as a matter of fact the experience of consumers with the somewhat more

complex mobile phone menus.

§

The focus group stimulated a debate among the participants, which was

focused on the ‘activate profile’ functionality. They were doubtful, whether

viewers will be using this functionality. Provision of targeted ads is

questionable as a form of adequate incentive. More likely, viewers will be

temped with personalization based on previous interactions and free sampling of

products.

§

The ‘contact me’ functionality, although useful as an immediate type of

interaction, was considered intrusive to the program –and advertisement- flow.

Alternatives such as auto-completion of the form fields and simple

interactivity overlaid to the program were suggested. The ‘bookmark’ functionality

was found very promising, although the term used (bookmark) should be revised.

Moreover, participants found no thematic distinction between the ‘contact me’

and ‘bookmark’ functionality, except from the level of immediacy. Finally they

were skeptical about the feasibility of the later-on interaction unless some

incentive or reminder is provided.

§

In addition to the interactive advertisement options during the regular

commercial, the participants got highly involved with the notion of interactive

content. The idea of a scaled down, in terms of complexity and number of pages,

web site was a favorite. Moreover participants stretched the importance of rich

multimedia and proposed a kind of low interactivity or ‘passive interactivity’.

Ideally, the interactive TV should eliminate the need

§

During the focus group session the horizontal theme of remote control

interactivity was continuously mentioned. A group of the participants was fond

of the cursor navigation, while an opposing point of view stretched for the familiarity

of the numeric keypad. Ideally, both methods should be tested with a

statistically significant sample of users. Furthermore, both methods could be

available as a system option to users.

Coaching Evaluation Key Findings

The main points

of the coaching evaluation results are summarized here, alongside with brief

participant profiles. We chose not to test thorough the profile form-fields and

functionality, because, as suggested by the focus group, it is a low frequency

task.

§

The single most important fact was the reconfirmation of the diffusion

of innovation theory. Technology aficionados belong in the innovators group and

welcome more or less everything that is new. Additionally, when asked for their

suggestions, they value customization, complexity and features. Next come the

early adopters group, who value convenience and ease of use, although they tend

to be fairly sophisticated users. This group, from a marketing point of view,

is the most promising one, as they tend to be opinion leaders for the majority

to follow. In our point of view, whatever user interface is offered to

innovators and early adopters will be considered adequate, assuming it is a

valid one. The challenge is how to lure into using the interactive features,

the early and late majority groups.

§

One more interesting aspect discovered through the in depth interviews,

was the different preferences relative to the interactive advertisement

options. The ‘contact me’ scenario was favored for products low in search

qualities and users with little computer experience, while the bookmark option

was preferred from middle-aged users and for products high in search qualities,

such as services or expensive and complex goods.

§

Last but not least, we have received some negative feedback about

various key system features. The terminology of the ‘contact me’ and ‘bookmark’

functionality was considered as poor and not descriptive of the related

feature. The ‘bookmark’ term was judged as irrelevant to the TV experience. The

rationale for this was based on the fact that TV is about entertainment and not

information search, in contrast to the web and library experience. According to

our test users opinions the difference between the two terms was based on a

time axis and not functional one. ‘Contact me’ is about impulse action, while

‘bookmark’ is about later and non-linear or asynchronous to the program flow

interactivity. Finally, TV viewers value highly the normal TV programming,

implying a need for associated services and not substituted to the current TV

features.

Interactive and

Personalized TV offers significant opportunities to advertisers, advertising

agencies, TV Channels but most importantly can turn passive viewers to active

participants, enhancing the TV viewing experience. The design of the viewer

interface has to deal with a number of challenging issues underlying the nature

of the medium and clearly traditional IS User Interface design struggles to

offer the experience required by TV Viewers.

In this paper we have presented our approach for the design of the

Interactive & Personalized TV-viewer interface and its application to

iMEDIA project. We attempted to present

the major forces affecting the user experience in the emerging field of the

interactive TV. These forces, more often than not, conflict with each other, so

we provided the parameters needed to balance the struggle among them. The

result of the user evaluation is a valuable set of issues raised by users,

mapping down alternatives, gained insights and revealed new issues, which can

be used towards the development of an interactive TV system that addresses

viewer needs.

Further research

would address the customization of the interface to accommodate diverse user

groups, the implementation of the experience gained by the patterns used in

mobile telephones as input devices, the minimization of the Viewer actions

needed to interact with the medium, the interface mechanism that simplifies the

process that users have to follow in order to declare their presence in front

of the TV set enabling the personalization of advertisements. Finally, an

important contribution would be the answer on what would be the most efficient

type of interactive advertisement (apart from the ‘bookmark’ and ‘contact’

type) that would allow the viewers to instantly interact with it and not

distracting their attention from the next advertising message.

Poon,

S. and Jevons, C. (1997) ‘Internet-enabled

International Marketing: A Small Business Network Perspective’, Journal of Marketing

Management 13: pp. 29-41.

Developer (1999) ‘What is Interactive TV?’,

http://developer.webtv.net/itv/whatis/main.htm, accessed 18/10/1999.

JoAnn T. Hackos and Janice C. Redish, User and

Task Analysis for Interface Design, John Wiley and Sons, 1998

Jakob Nielsen, Usability Engineering, Morgan Kaufmann,

1993

Hobbs, J.

Functionality On-Demand Software Architecture for Wearable Computers.

Available at http://www.cs.uoregon.edu/~kortuem/Papers/fod

Preece, J, Human-Computer Interaction, Reading, MA,

Addison-Wesley, 1994

Preece J, Keller S, Why What and How? Issues in the

development of an HCI training course, Cambrigde, 1994

Bevan N, Brigham F, Harker S, Yourmas D, Usability

assurance and standardization, 1990

Hix D, Hartson R, Human Computer Interface

Development: Concepts and systems for its

management, 1993

Dix, A., J. Finlay,

Human Computer Interaction, Toronto, Prentice Hall,1996

http://www.lboro.ac.uk

Ben Shneiderman, Designing the User Interface:

Strategies for effective Human Computer Interaction, Addison Wesley, 1998

Ballay, J.M., Designing Workscape: An

Interdisciplinary Experience, Proceedings of CHI '94, Boston, pp. 10-15

Nielsen, Jakob and Mack, Robert (Editors),

Usability Inspection Methods, John Wiley and Sons, 1994

Stephanie

Ludi, Macromedia Director as a Prototyping and Usability Testing Tool, www.acm.org/crossroads/xrds6-5/macromedia.html

Gerard

O’Driscoll, The Essential Guide to Digital Set-top Boxes and Interactive TV, Prentice Hall, 2000

Jacob

Nielsen, The art of navigating through hypertext, Communications of the ACM,

March 1990

Jacob Nielsen , Ten Usability Heuristics,http://www.useit.com/papers/heuristic/heuristic_list.html

Frank

Rose, TV or not TV, Wired 8.03, March 2000

Donald

Norman, The Invisible Computer: Why good products can fail, the Personal

Computer is so Complex and Information Appliances are the Solution, MIT press, October 1999

Sherry Turkle, Life on the Screen: Identity in

the Age of the Internet, Touchstone Books, September 1997

Byron

Reeves, Clifford Nass, The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers,

Television and New Media Like Real People and Places, Cambridge University

Press, June 1999